Summary of my sermon, based on Genesis 22:1-14. Preached at Greenhills Christian Fellowship York on August 31, 2025.

Music captures attention, sets the tone, stirs the affections, and helps us remember truth. The Psalms repeatedly command it: “Oh sing to the Lord a new song.” Many Sundays we might forget a sermon outline but carry a line of a hymn all week. That’s not an excuse for poor preaching; it’s a reminder of how powerfully God uses singing in worship.

To think more deeply about worship, we turn to the first mention of the word in Scripture: Genesis 22. There we learn, first, that worship is a response. God speaks, and Abraham answers, “Here I am” (Gen 22:1). We don’t initiate worship; God calls, commands, and invites. Romans 12:1 says, “Therefore… present your bodies… this is your spiritual worship.” The “therefore” points back to who God is (Rom 11:33–36). He deserves it.

Second, worship requires preparation. Abraham rose early, saddled the donkey, split the wood, selected companions, and traveled three days (Gen 22:3–4). Leaders prepare setlists and slides; musicians practice for years. But all of us must also prepare our hearts. Life distracts and wounds. That’s why Jesus says, “Come to me… and I will give you rest” (Matt 11:28–30).

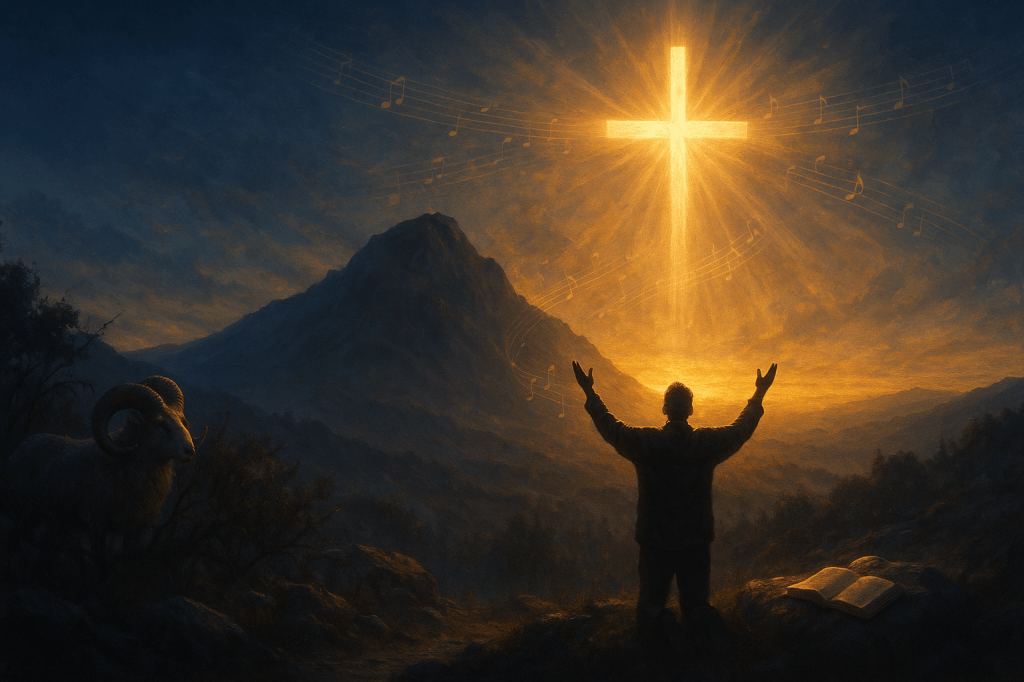

Yet here’s the heart of it: Worship is Christ-centered. On the way up Moriah, Abraham told his servants, “I and the boy will go… we will worship, and we will come again” (Gen 22:5). How could he say that when God had commanded him to offer Isaac? Hebrews 11 explains: Abraham considered that God could raise the dead (Heb 11:17–19). And when the knife was raised, God provided a substitute—a ram caught in a thicket (Gen 22:11–13). Moriah points us to Calvary, to the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world.

Jesus is our Passover Lamb (John 1:29; 1 Cor 5:7). “He was pierced for our transgressions… and by his wounds we are healed” (Isa 53:5). Because he “became obedient to the point of death—even death on a cross,” God “highly exalted him,” so that at the name of Jesus every knee bows and every tongue confesses he is Lord (Phil 2:8–11). We worship Jesus not merely because he inspires us, but because he saved us. The cross is the ground of his unique worthiness and the reason heaven’s song declares, “Worthy is the Lamb who was slain” (Rev 5:12).

Left to ourselves, our hearts are “idol factories,” crafting gods in our own image or offering God lip service while our hearts are far away (Matt 15:7–9). The cross changes that. There, Jesus not only purchases our forgiveness; he wins our affection and grants us access. The cross is the objective evidence of God’s love. Whatever burden you carry—grief, doubt, the “dark night of the soul”—hear his invitation: “Come to me… and I will give you rest” (Matt 11:28). Because God’s wrath was poured out on Jesus, there is none left for those in him. So we don’t just admire Christ—we are drawn to adore him. The Spirit takes the finished work of the Son and turns reluctant people into willing worshipers.

Lift your eyes, then, from Moriah to heaven’s throne room: “Worthy is the Lamb who was slain… To him be blessing and honor and glory and might forever and ever!” (Rev 5:11–14). That is where our singing on earth is headed.

In summary: Worship begins as God’s call and our response, deepened by intentional preparation. But it finds its center and power in Christ crucified and risen. We worship because of the cross—Jesus is worthy—and we worship through the cross—Jesus makes us willing and able. Turn your eyes upon Jesus; look full in his wonderful face, and let the things of earth grow strangely dim in the light of his glory and grace.