Summary of my sermon, based on Hebrews 10:19-25. Preached at Greenhills Christian Fellowship Toronto on January 4, 2026.

Our confidence before God doesn’t come from a spiritual “winning streak” or perfect routines, but from Jesus. Think about confidence the way a team’s championship odds change: they move when wins are on the board. In the Christian life, the decisive win is Christ’s finished work—not our day-to-day highs and lows. He lived sinlessly, died in our place, rose in power, and now brings us into the Father’s presence.

“Therefore, brothers and sisters, since we have confidence to enter the holy places by the blood of Jesus… let us draw near with a true heart in full assurance of faith” (Hebrews 10:19, 22, ESV). That is the bedrock of assurance.

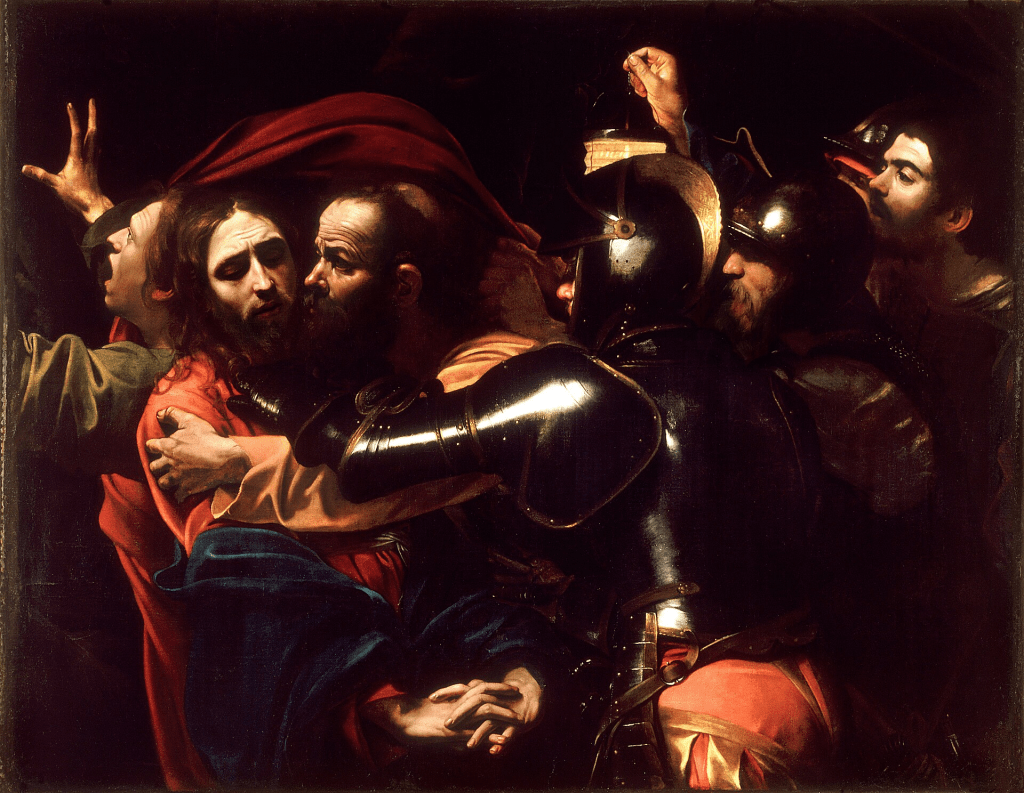

Why did we ever need such confidence? Because God’s holiness and our sin create a real separation. In the Old Testament, only the high priest entered the Holy of Holies, only once a year, and only with cleansing and sacrifice (see Leviticus 16). The tabernacle curtain embodied that barrier. But when Jesus died, “the curtain of the temple was torn in two, from top to bottom” (Matthew 27:51, ESV). By His blood, the way is open. Now we draw near with hearts made clean and bodies washed (Hebrews 10:22).

Two distortions erode that gift. First, “Jesus plus.” We start believing we’re accepted because of Jesus and our devotions, attendance, giving, or serving. Those are good fruits, but they are not the root. We don’t add to the cross; we respond to it. Second, trusting the strength of our faith rather than the Savior. Doubts come, trials shake us, and we worry our weak faith disqualifies us. But even “faith like a grain of mustard seed” moves mountains (Matthew 17:20, ESV). Like the desperate father, we pray, “I believe; help my unbelief!” (Mark 9:24, ESV). Our confidence rests in Christ Himself; He strengthens and guards us.

On that foundation, Hebrews gives a clear, practical call: “Let us hold fast the confession of our hope without wavering, for he who promised is faithful” (Hebrews 10:23, ESV). And then: “Let us consider how to stir up one another to love and good works” (v. 24). That little phrase “consider how” matters. It’s intentional attention, not accidental encouragement. To “consider” is to notice a brother’s burdens, a sister’s gifts, and think creatively about what would actually help them take the next step toward love and obedience.

That kind of thoughtful care requires proximity. So Hebrews adds: “not neglecting to meet together, as is the habit of some, but encouraging one another, and all the more as you see the Day drawing near” (Hebrews 10:25, ESV). Streaming is a grace when illness, weather, or distance intervene; but as a rule, embodied fellowship is the ordinary means God uses to grow us. In the room we see each other’s eyes, hear the real tone beneath the “I’m fine,” and obey the Spirit’s nudge to pray, serve, give, or simply listen. The church isn’t a content platform; it’s a Spirit-filled people.

So what does “considering how to stir up” look like this week? Notice who seemed weary on Sunday, who rejoiced, who was missing. Act with a text, a call, a visit, a meal, a prayer, or a practical offer to help. Aim at love and good works; encouragement isn’t mere compliments, it’s oxygen for obedience.

And when we gather at the Lord’s Table, we rehearse the source of our confidence again: Christ’s body given, Christ’s blood shed—for you, for us. Communion is not a reward for the strong but nourishment for the weak who are clinging to Jesus. It recenters our assurance on His finished work, and it rekindles our commitment to “one another” life.

Come boldly—not because you’re on a roll, but because Jesus reigns. Hold fast—not because you never wobble, but because He never wavers. And look around the room—there’s someone God is asking you to “consider” this week. Encourage them toward love and good works until the Day dawns.