Summary of my sermon, based on 2 Corinthians 13:12. Preached at Greenhills Christian Fellowship Toronto on November 3, 2025.

How do you view greeting? For many of us, it’s probably not something we think about very much. Among my friends and colleagues—even my manager—it’s not really something we think about. Usually for me, it’s just a simple “what’s up,” because I grew up in Scarborough in the late 90s. That was our thing back then. For the most part here in the West, it’s not something we think of very often.

That’s not the case in other countries. Recently I came across a reel about greetings in Japan where, depending on your status relative to the person you’re greeting, there are various appropriate ways to greet. If you happen to see the president of your company in the morning, the appropriate greeting would be “Ohayougozimashita”—the longest, most polite form of “good morning.” For a manager it might be “Ohayougozaimasu,” for a senpai it’s simply “Ohayou,” and for a friend or colleague it can be as short as “Sus.” In general, the longer the greeting, the more polite and formal; the shorter, the more casual. Japan is much more rigidly structured in that way than the West.

Something else I found on the interwebs: people crashing out on LinkedIn over how you greet someone on the phone. One recruiter from North Carolina posted (in all caps): “I returned the candidate’s call. His first words shocked me.” The candidate had left a very professional message, a high-level profile, but when the recruiter called back (from the same number), he answered, “Hello.” Apparently that mattered a lot. The recruiter couldn’t understand why professionals answer without saying who they are. As you can imagine, the post was met with ridicule. My favorite reply: “It’s obviously unacceptable to answer just ‘hello.’ You have to say, ‘Hello, is it me you’re looking for?’” (Yes, that’s Lionel Richie.)

In all seriousness, while LinkedIn recruiters may be a little overzealous, greetings do matter. They matter enough that the Apostle Paul commanded Christians how to greet one another. This is one of the “one another” commands we’re covering: “Greet one another with a holy kiss.” (2 Corinthians 13:12, ESV) Paul repeats it in Romans 16:16; 1 Corinthians 16:20; 1 Thessalonians 5:26. Peter echoes it with a slight variation: “Greet one another with the kiss of love.” (1 Peter 5:14, ESV)

Depending on your cultural background, that may sound strange. But in Toronto, this might not be so foreign. Think of the Kennedy Kiss & Ride—a staple in Scarborough culture. It captures the idea: not an erotic kiss, but a simple greeting (often a cheek-kiss). In North America, that’s not predominant anymore; in parts of Europe, Latin America, and the Middle East, it still is. In the Philippines there’s the “besso-besso”. But, even within one culture, families vary. On my mom’s side, we greet elders with a kiss on the cheek (I don’t “mano” my Lola; I kiss her as a greeting). On my dad’s side, it’s different. Not better or worse—just different.

The key point: kissing has been, and continues to be, a common greeting in many parts of the world, especially among family and close friends. A biblical example appears in Acts 20 when Paul says farewell to the Ephesian elders: “And when he had said these things, he knelt down and prayed with them all. And there was much weeping on the part of all; they embraced Paul and kissed him, being sorrowful most of all because of the word he had spoken, that they would not see his face again.” (Acts 20:36–38, ESV)

That brings us to the adjective holy. What does a holy kiss mean? One way to understand it is by its opposite: unholy kisses.

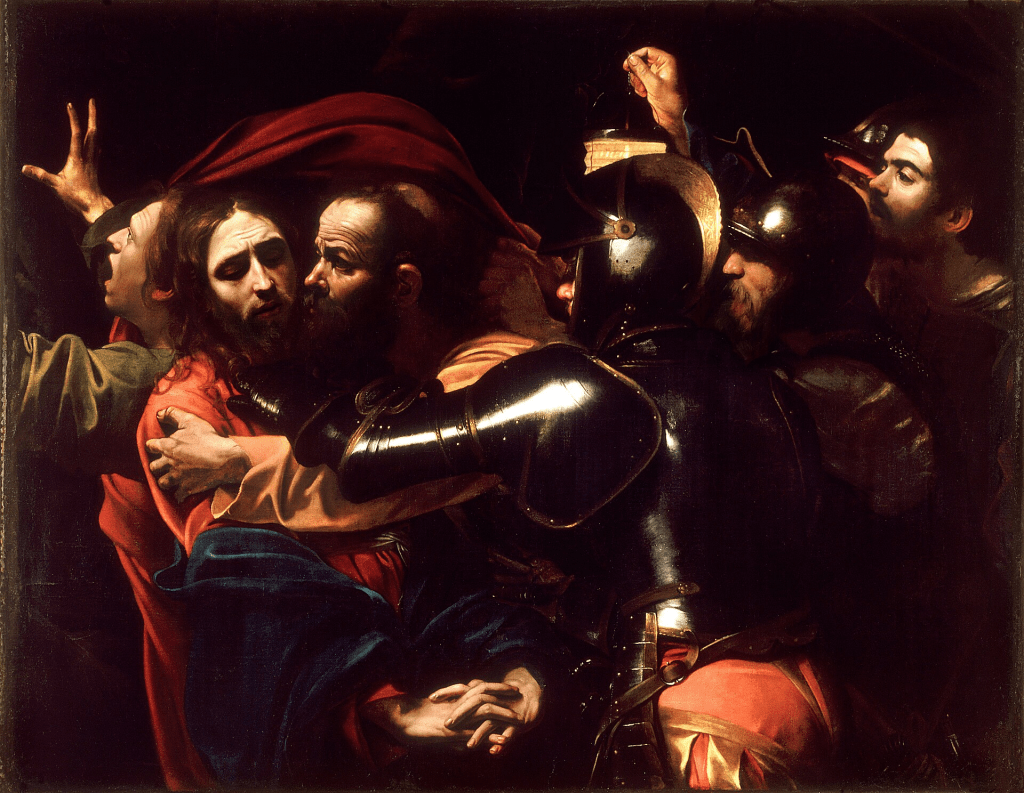

The most infamous unholy kiss is Judas’s betrayal: “Now the betrayer had given them a sign, saying, ‘The one I will kiss is the man. Seize him and lead him away under guard.’ And when he came, he went up to him at once and said, ‘Rabbi!’ And he kissed him. And they laid hands on him and seized him.” (Mark 14:44–46, ESV)

Another unholy kiss is a kiss of deception in 2 Samuel 20. After David replaced Joab with Amasa, Joab met Amasa on the road: “And Joab said to Amasa, ‘Is it well with you, my brother?’ And Joab took Amasa by the beard with his right hand to kiss him. But Amasa did not observe the sword that was in Joab’s hand. So Joab struck him… and he died.” (2 Samuel 20:9–10, ESV)

In the church, we may not often face outright betrayal, but we can be tempted to deceive—to greet warmly while harboring jealousy, anger, or bitterness. Paul instructs us otherwise: “Let all bitterness and wrath and anger and clamor and slander be put away from you, along with all malice. Be kind to one another, tenderhearted, forgiving one another, as God in Christ forgave you.” (Ephesians 4:31–32, ESV)

That is the content of a holy greeting: kindness, tenderheartedness, forgiveness. A beautiful picture of a holy kiss appears in Jesus’ parable of the prodigal son: “But while he was still a long way off, his father saw him and felt compassion, and ran and embraced him and kissed him.” (Luke 15:20, ESV)

It is a kiss of forgiveness and grace, overshadowing great wrong. I think Paul had this kind of grace in mind when he urged the Corinthians to greet one another with a holy kiss—especially given his painful history with them. He had confronted sexual immorality, greed, idolatry, slander, adultery, and divisions. He wrote a hard letter and made a painful visit. Then he explained:

“For I made up my mind not to make another painful visit to you. For if I cause you pain, who is there to make me glad but the one whom I have pained?… For I wrote to you out of much affliction and anguish of heart and with many tears… to let you know the abundant love that I have for you.” (2 Corinthians 2:1–4, ESV)

So when Paul says “greet one another with a holy kiss,” he means: you are family now. Show closeness and affection in a way that fits the gospel you believe and the salvation you’ve received in Christ.

In closing, I’m not saying we need to start kissing each other as part of our greetings. We’re in Canada; that’s not our common form. But we should practice whatever is culturally appropriate to show we are not mere acquaintances—we are the family of God, brothers and sisters in Christ. Our greetings should be affectionate and reflect our relationship to each other. They should not be unholy or deceitful, hiding things that need to be addressed. They should be genuine and true, holy, and filled with the self-sacrificing grace and love Christ showed us when he died on the cross—a gospel we remember especially when we celebrate the Lord’s Supper.